Awhile ago, I posted a thread on rapid sequence induction since I felt my paramedic program didn't go a good job covering (ie "You'll never do this... *click* *click* *click*...). Linuss recommended that I read Manual of Emergency Airway Management, which I am still in the middle of. One point that the book kept bringing up in the first few chapters is being prepared to have alternative ways to manage the airway, recognizing CICO, and to move onto a needle or regular cricothyrotomy. I was just browsing Facebook when I saw the Facebook group Prehospital 12-lead ECG post a video on "Can't Intubate, Can't Ventilate" (same thing as CICO) and the Tac-Med LLC posted below with a video of a cricothyrotomy.

Oddly Veneficus just posted his thoughts on videos and simulators,and I definitely believe we put too much emphasis on 'em and minimized or replaced doing the real thing, but I still think videos and simulators are a good adjunctive learning tool which is why I've decided to share what I saw on my Facebook here.

Video of Can't Intubate, Can't Ventilate: http://vimeo.com/970665

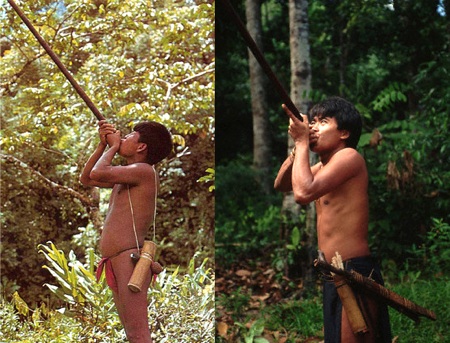

[YOUTUBE]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yfyQP4wNbcA[/YOUTUBE]

When do you think we should give up on intubation? Gut feeling? Number of attempts? Difficulty (Mallampotti and/or Cormack & Lehane)? Do you even know the Mallampotti and Cormack & Lehane scale?

Do you have a backup plan for when plan A fails? Do you have alternative airways ready? Different sizes ready? Do you know different techniques to insert these airways? Is this feasible in the prehospital setting?

In the video, the anesthesiologists and ENT failed to recognize CICO, but the nurses did recognize it, informed the ICU, and grabbed the cricothyrotomy kit, yet they never spoke up to actually discontinue attempting to insert an endotracheal tube even after 30-something minutes! How do you think somebody would react if somebody equal or lower in training/certification said to you "This isn't going to work. It's cricothyrotomy time"? What are ways that we can approach somebody who is equal or higher training to us who are tunneled vision? A lot of people also mention that they'll speak up if somebody is doing something detrimental to the patient, but to me, it seems like people rather wait until after everything happens before they speak up (even if it's detrimental to the patient).

Relevant Links:

Manual of Emergency Airway

Rapid Sequence Induction HOWTO

"I saw it on TV..."

Prehospital 12-Lead ECG (ems12lead) Facebook Group

Tac-Med LLC Facebook Group

Oddly Veneficus just posted his thoughts on videos and simulators,and I definitely believe we put too much emphasis on 'em and minimized or replaced doing the real thing, but I still think videos and simulators are a good adjunctive learning tool which is why I've decided to share what I saw on my Facebook here.

Video of Can't Intubate, Can't Ventilate: http://vimeo.com/970665

[YOUTUBE]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yfyQP4wNbcA[/YOUTUBE]

When do you think we should give up on intubation? Gut feeling? Number of attempts? Difficulty (Mallampotti and/or Cormack & Lehane)? Do you even know the Mallampotti and Cormack & Lehane scale?

Do you have a backup plan for when plan A fails? Do you have alternative airways ready? Different sizes ready? Do you know different techniques to insert these airways? Is this feasible in the prehospital setting?

In the video, the anesthesiologists and ENT failed to recognize CICO, but the nurses did recognize it, informed the ICU, and grabbed the cricothyrotomy kit, yet they never spoke up to actually discontinue attempting to insert an endotracheal tube even after 30-something minutes! How do you think somebody would react if somebody equal or lower in training/certification said to you "This isn't going to work. It's cricothyrotomy time"? What are ways that we can approach somebody who is equal or higher training to us who are tunneled vision? A lot of people also mention that they'll speak up if somebody is doing something detrimental to the patient, but to me, it seems like people rather wait until after everything happens before they speak up (even if it's detrimental to the patient).

Relevant Links:

Manual of Emergency Airway

Rapid Sequence Induction HOWTO

"I saw it on TV..."

Prehospital 12-Lead ECG (ems12lead) Facebook Group

Tac-Med LLC Facebook Group